How we come back

How we come back

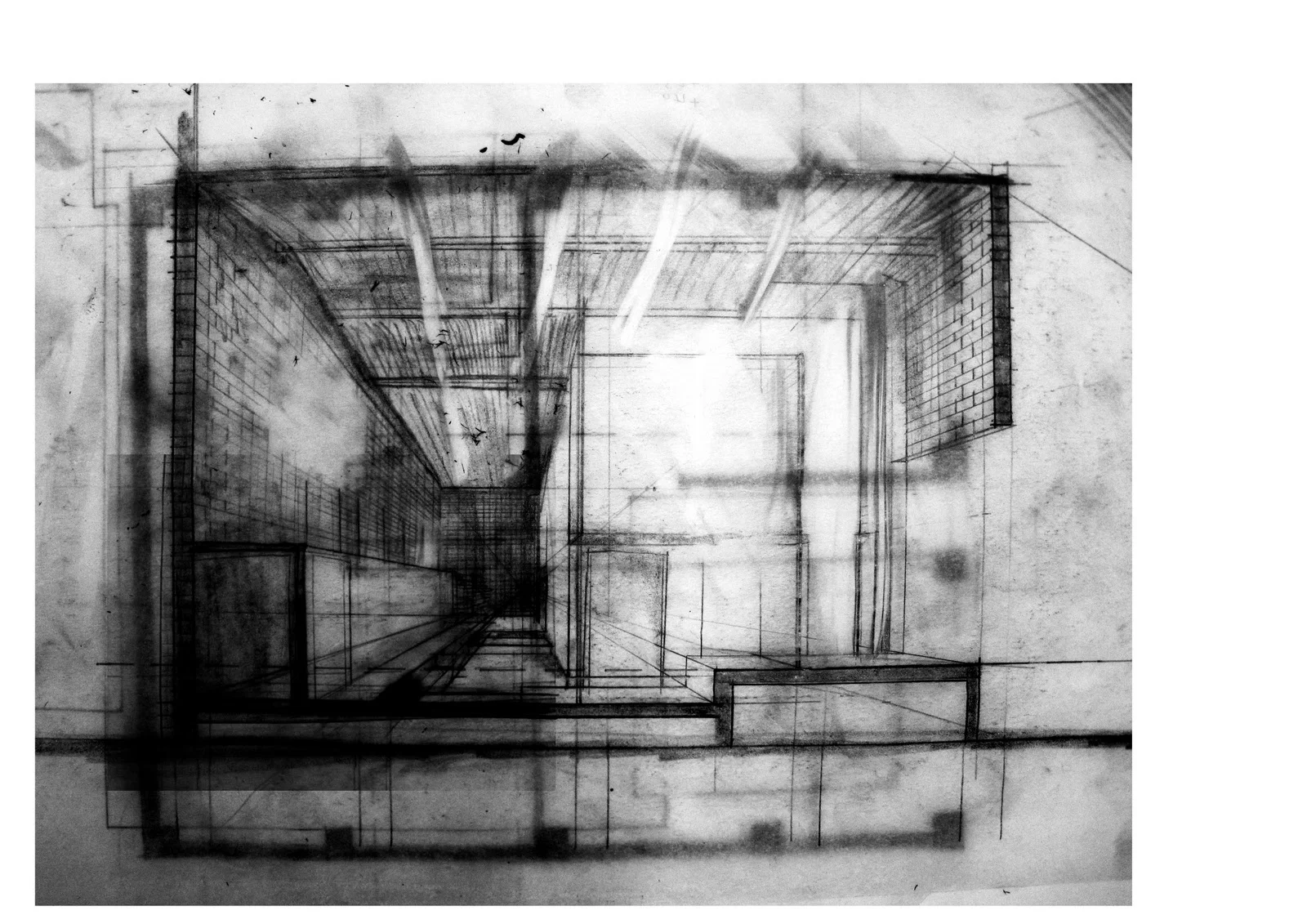

Sketches of the Musee d’Orsay, August 2017

As a child, you can get close enough that the strokes become strong and dissolve the image. This close, you don’t need much imagination. You see plants, you see their reflections. You quickly forget the room around you.

I remember that feeling of trying to tie it all together with what I had learnt of lilies. I had studied them at the local horticultural hall in preparation, yet the way the canvas seemed to expand made it difficult to understand. There was no horizon, no sky, nothing else beyond the plants in their water. Just atmosphere and my breath, slow against the blues.

——————

This isn’t a complicated tale, except for the way it layers. There’s a particular way the mind, transcribing moments, sets them down as translucent sheets atop one another. Or, to picture it differently, if each journey is a canvas, each canvas is disguised by the brush that traces its surface. The composition of any memory is a painterly mix. It’s when you look back, trying to separate the coats, that the edges of time begin to curl, and the layers begin to separate strangely. I’ve spent hours trying to squint into this space, to unfurl the beginning of my journey. Things come in and out of focus quickly. They’re all just impressions. It feels like an impossible thing but I keep trying to hold it all at once.

Sometimes it feels simplest to start historically. But with whose history? I could always start by tracing my own footsteps, to go back to that surreal age when nothing bad had ever happened to me. What do I remember? An art teacher with a kind face. A mother who encouraged. The hues of the summer sun setting in the south, seen through a slit in the purple patterned curtains, when I was supposed to be sleeping.

One moment in particular comes to mind: my small body close to the wooden floor, the space gold-tinted, perhaps by the sun, or perhaps by the light of a lamp on the desk to the left. Newspapers spread, open across the floor, with large, thick rectangles of white paper arranged on top of them. Hunched over one of them, my whole arm sweeping across the surface, I painted in thick, bold strokes. Those paintings are still in the attic, somewhere, curling under the weight of the golden grasses, dense sunsets, and the deep blue shadows I had understood from my copy of the History of Impressionism.

That’s the first reminder that my history isn’t all mine. In 1986, three years before I was born, a building on the banks of the Seine was reincarnated. Actually, the process was slower and undoubtedly more tumultuous than those words make it seem. Many were not convinced by the unnatural transformation of the Beaux-Arts building, finding something awkward in the way the new interior filled in the precious voids, disguising the structural strength.

When I arrived here for the first time, and stood at the bottom of the spectacular space that is known as one of Paris's great 19th-century rooms, I wasn’t aware of the architectural criticisms, the historic correctness. At twelve years old, in Europe for the first time, I found my eyes catching on the sparkling edges of things. I must have walked around on tiptoes, trying to get to the centre of things. Mostly, I found, you can imagine what things might have been. A paving stone here, an entry there, the great cavernous belly now filled with bodies - bronze, stone and the living - instead of the engines of steam trains. And at night, an image history can’t shake: the glowing face of the great clock telling you the time.

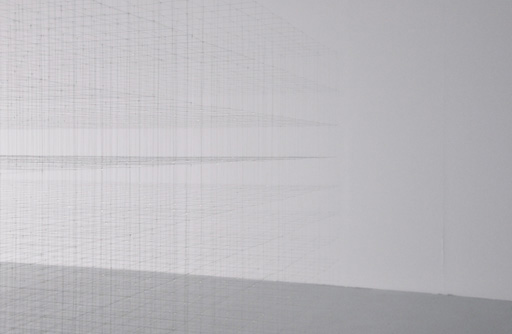

On the flanks, in this new arrangement, there are hidden spaces that I now think only the curiosity of a child opens, galleries you couldn’t hope to find without a map. I remember getting lost, the delight of it. Even now, this is the most visceral of memories. Not the open space, but being held captive against the darkened corners under the soaring barrel-vaulted glass ceiling: vivid and atmospheric, shot through with light.

——————

There’s another history here, too, one which starts more than a century earlier in 1840, and slightly North of where we are now, on Rue Laffitte in the 9th Arrondissement. As a young girl kneeling over my painting I could have told you that, and how the story would take us further North still, to Le Havre, then beyond to Africa, London, and Vétheuil. And finally, to a place first seen while looking out the window of a train, and later immortalised in the Nympheas Bleus. Giverny.

How can we measure such a journey? As a station becomes a gallery, a child becomes an adult, a painter a memory of his strokes - by the movement, the motion, the way we travel?

——————

The second time I stood beneath the roof I was with friends, but I found myself alone, standing slightly to the left of his Gare St. Lazare: an enclosed urban interior, but somehow also a scene of travel, an echo of each engine’s movement across a landscape. The image itself seemed to be formed from steam, those thick wet strokes, the space of the canvas erupting, the illusion of depth. And the light seeping out.

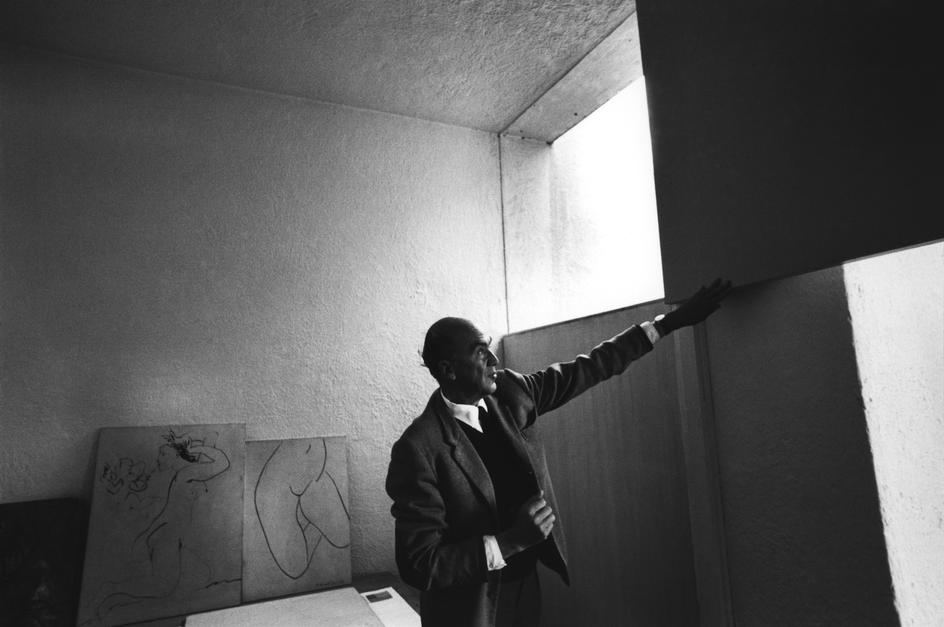

In painting, a traditional approach is to plan the work section by section, allowing each to dry - often a process requiring days at a time - before continuing with the next. The reworking of an existing but neglected building is similar. There is a lot of waiting and you can’t be sure how it will turn out, despite your plans. That process requires disassociation, pocketed emotion. You cannot paint what you see - not if what if you see is how you feel, and how you feel is where you have been. To paint en plein air, in the poppy field or the station, you must be there, really there. Sometimes I think there must be a way of folding physical space with the feeling of being. This story is the closest I can get to some kind of evidence.

——————

I’ve been here three times now. One visit for each of my journeys to France, one for each decade - although they don’t quite distribute that way. I never remember lining up, the tickets or people. Just the proximity - my flesh against the bronzed figures in the lofted volume. And always, the light above.

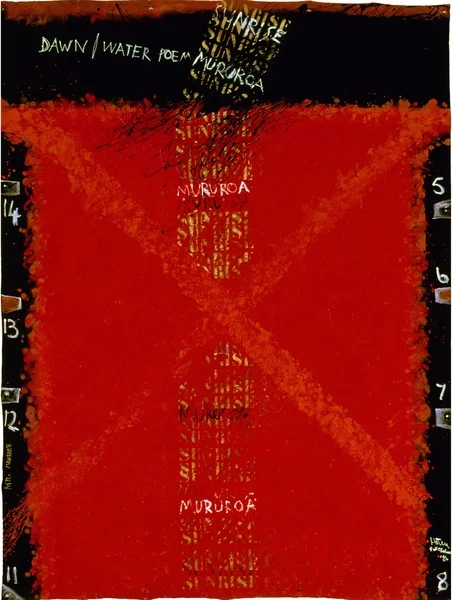

They might have told you otherwise but I think maybe this is how we might best measure a journey - the ways we understand light differently. Each history, then, as a journey, a travelling of light. And when they intersect, well, I still can’t tell you which is which, or where one stops and the other begins. Sometimes I’m not so sure they’re different at all.

I remember being outside, waiting, the rain on my leather shoes - it must have been the second time. Barricades stopping the crowd from pouring into the traffic, the unadorned stone facade darkening in the dampness. The way everything smelt damp, as if the water had released an entire history from the cobbles. Later I crossed the bridge and turned back to see the clock face and, there, between me and it, l’arc en ciel. Sometimes there is magic in reality. Sometimes time has a way of configuring things.

——————

The last time I went it was early on a winter evening, and darkness had already fallen. And it was the quiet, stolen hour of the Parisians who, after work, wander the gallery as a kind of urban meditation. When I arrived I found the space resonating, the notes from a pianist outside filling up the chambers.

I left after an hour or two, crossed the river and walked to the north west, to the canals. There, I ate in the dining room of family. In the room with two doors and one window, we were a family with two countries and two languages. Outside the window was a narrow balcony overlooking the street. As I ate, all I could think of were distances and journeys.

Later that night, on the balcony of my own studio in the 14th Arrondissement, I realised it was never a building I was supposed to love. But I could not extract it from what it means to be a painter, an architect, a citizen, or, now from what it means to be myself. Like Monet I find myself coming back to "things that are impossible to do…”. I am trying to tie these threads together.

——————

In the gift shop before we left, my parents gifted me some francs. With them, I purchased small a calendar. When we arrived home at the end of June I stood the calender in the corner of my desk. I waited patiently for January and then, at the end of each month for a year, I would flip it over to reveal a different painting. I bought it thinking it would be a way to grow up, that I could plan my life by it. My birth month of May was the Nympheas. I thought it meant I was limitless.

——————

Sometimes, we cannot extract ourselves from the journey of light. This is how we come back.